Preface

Abbreviated Sources

and References

Annotations: title, epigraph and dedication

Part I

Part II

Part III

![]()

Influence and authenticity of

l'Inconnue de la

Seine

By Anja Zeidler

During the first decades of the 20th century, copies of a young woman's death mask were widely sold in France and Germany and hung on the walls of many homes. Enchanting all with her "smile of sublime satisfaction," (Phillips, 321), the mask was known as the Inconnue de la Seine, and inspired a remarkable number of literary works, especially during the 1920s and 1930s. The story was that around the turn of the last century, the body of a young woman was recovered from the Seine near the quai du Louvre (Vautrain, 550). (Sacheverell Sitwell dates her death earlier because of her hair style, which he thinks reflects the fashions of the mid-nineteenth century: "My own feeling is that her hair is that of a peasant girl, a poor shop girl, or that of a beggar or vagrant, and that her body was found in the Seine at the end of the 'seventies or early 'eighties" (Sitwell, 316).)

The drowned woman was taken to the Paris Morgue for identification. At that time it was located behind Notre-Dame at the eastern tip of the Ile de la Cité, quai de l'Archevêché, where the unknown dead were displayed for the public to see and, it was hoped, identify. The Paris Morgue was a famous institution during its time, and attracted thousands of visitors every day until it closed in 1907. Here "the allegedly serious business of identifying anonymous corpses [turned] into a spectacle […] – in the French double sense of theater and grand display" (Schwartz 47, 59). Its administrators regarded the morgue as a Paris attraction. Whether the unknown young woman was publicly exhibited at the morgue is not part of the story, though: however it was said that her smile was so compelling to a medical assistant at the morgue that he took an impression of her face, and the great numbers of plaster casts produced and sold came from this unknown young woman's death mask.

"During the 20s and early 30s, all over the Continent, nearly every student of sensibility has a plaster-cast of her death-mask" (Alvarez, 156) -- and also later: Albert Camus (1913-1960), for example, is said to have loved to show his favorite sculptures, among them "un moulage du touchant visage de l'Inconnue de la Seine, au sourire de Joconde noyée" ("a cast of the touching face of the l'Inconnue de la Seine, with the smile of a drowned Mona Lisa," Boddaert, 137). The poet Jules Supervielle (1884-1960), born in Montevideo to French parents, also owned a mask, according to his daughter (Pinet, 190) and wrote a rather fantastic story ("L'Inconnue de la Seine," 1931) from the viewpoint of the 19-year-old drowned woman as she is moved by the Seine's current towards the sea:

"Elle allait sans savoir que sur son visage brillait un sourire tremblant mais plus résistant qu'un sourire de vivante, toujours à la merci de n'importe quoi" ("She traveled not knowing that on her face shone a trembling smile, far more unremitting than the smile of the living, which is always at the mercy of whatever may come," Supervielle, 66).

Telling the "Grand Mouillé" (the Great Wet One) that she knows nothing about herself any longer, not even her name, he names her "l’Inconnue de la Seine" (69). However, to live in the new environment she must stay at the bottom and follow certain rules, and she doesn't want rules: her wish to “mourir enfin tout à fait” (finally die for good, 80) makes her swim to the surface where suffocation is sure to come.

Other famous writers were associated with the mask. Maurice Blanchot (1907-2003) had a cast in the room he used most often in his tiny house in the village Eze on the Côte d’Azur, where he lived from 1947. He describes it as

“une adolescente aux yeux clos, mais vivante par un sourire si délié, si fortuné, […] qu'on eût pu croire qu'elle s'était noyée dans un instant d'extrême bonheur” (an adolescent with closed eyes, but enlivened by a smile, so relaxed, so rich that one may be led to believe that she died in a moment of extreme happiness, 15).

Blanchot also mentions Giacometti being enchanted by the mask. In 1933 Louis-Ferdinand Céline was asked for a photograph of himself to accompany his text "L’Église" in a collection. Instead Céline gave a photograph of Le Masque de l’Inconnue de la Seine (Pinet, 179) to his editor. And around the beginning of the 20th century, Rainer Maria Rilke’s autobiographically inspired narrator in Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge (The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge) passed the mask every day:

"Der Mouleur, an dem ich jeden Tag vorüberkomme, hat zwei Masken neben seiner Tür ausgehängt. Das Gesicht der jungen Ertränkten, das man in der Morgue abnahm, weil es schön war, weil es lächelte, weil es so täuschend lächelte, als es wüßte." (65) ("The mouleur, whose shop I pass every day, has hung two masks beside his door. The face of the young drowned woman, a cast of which was taken in the Morgue because it was beautiful, because it smiled, smiled so deceptively, as though it knew," 70).

Apparently the first literary text about the smiling death mask is a short novella by a popular British writer Richard le Gallienne, who owned a copy of the mask (Phillips, 322), written in 1898 and published in 1900. In The Worshipper of the Image, Antony is a young and sensitive poet living in an isolated châlet in a clearing in the woods. He comes under the malevolent influence of the famous death mask: when, from the Covent Garden shop owner who sold him the cast, he brings home to his wife Beatrice and his four-year-old daughter Wonder the story "that the sculptor who moulded [the mask] had fallen so in love with the dead girl that he went mad and drowned himself in the Seine also." And that course of events repeats itself: Antony finds himself drawn to the mask more and more and even invents a name for her, Silencieux. "Every day new life welled into Silencieux's face, as every day life ebbed from the face of Beatrice." The poet becomes equally estranged from his child and eventually, because of his obsessive love of this image, to whom he talks and who talks back to him, he sacrifices the life of his daughter, who falls ill ("The doctor gave the disease no name") and dies. Even though the shock of her death brings him back to his wife briefly ("You are an evil dream that has stolen from me the truth of life" he tells the mask), he soon comes under Silencieux's spell again and Beatrice drowns herself in a river. "Poor little Beatrice," Antony comments at the very end of the story,

but how beautiful! It must

be wonderful to die like that. And then again he said: 'She is strangely

like Silencieux.' Then he walked up into the wood, in a great serenity of mind.

He had lost Wonder, but she lived again in his songs. He had lost Beatrice,

but he had her image -- did she not live for ever in Silencieux?

So he went up into the wood, whistling softly to himself -- but lo! when he opened his châlet door, there was a strange light in the room. The eyes of Silencieux were wide open, and from her lips hung a dark moth with the face of death between his wings.

The Inconnue had a haunting effect on the imagination of many authors. In Claire Goll's story "Die Unbekannte aus der Seine" (The Unknown of the Seine, 1936), the painter Armandier dies suddenly of a heart attack when he sees the mask of the Inconnue in a small shop near Notre Dame and it reminds him of his great love Corinne and her last smile before separation: in a flash of recognition, he comes to believe this is the face of their daughter, of whose existence he at that instant thinks for the first – and sadly the last – time. The narrator of Anais Nin’s dreamlike story "Houseboat" (1944), where the river is the main symbol, knowing the “mystery of continuity” (34), emptying "one of all memories and terrors" (33), points a revolver out of the window of her houseboat on the Seine -- with an uneasy feeling, " as if I might kill the Unknown Woman of the Seine again – the woman who had drowned herself here years ago and was so beautiful that at the Morgue they had taken a plaster cast of her face" (35).

The first factual report on the mask and a photo of it came far later, in 1926, in Das ewige Antlitz, a book of 123 death masks published by Ernst Benkard. In his description of this mask he lapses into a highly poetic tone uncharacteristic of his comments about the other masks:

"Uns jedoch ein zarter Schmetterling, der, sorglos beschwingt, an der Leuchte des Lebens seine feinen Flügel vor der Zeit verflattert und versengt hat." ("To us she is a delicate butterfly, who – winged and lightheartedly – had her tender wings prematurely singed," 61).

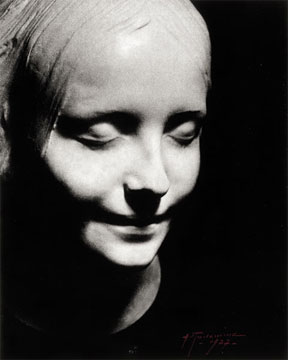

By 1935 the book had gone through 19 printings and had been translated into English and other languages (Johnson, 230). Soon after, in 1929, another book of death masks – Das letzte Gesicht – including the Inconnue was published. There it is claimed that the index of the Paris Morgue lists her under the name l'Inconnue de la Seine. The photographer Albert Rudomine (Kiev 1892--Paris 1975), who had a portrait studio at the Boulevard de la Tour Maubourg, made a photograph of the Inconnue in 1927 (below), using the same play of shadow and light he used for his portraits of actors of the same period (Pinet, 185). It’s title, La Vierge inconnue, canal de l’Ourcq, is a conflation of the l'Inconnue de la Seine and the virgin Mary, as well as a reminder of the number of suicides in the canal de l'Ourcq reported in the press at the time.

Jules Supervielle

Maurice Blanchot

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Rainer-Maria Rilke

Richard le Galienne

Claire Goll

Anais Nin

Elisabeth Bergner

Muschler's Unbekannte

Hertha Pauli

Ödön von Horváth

Man Ray

Louis Aragon

In the The Savage God. A Study of Suicide Al Alvarez writes: "I am told that a whole generation of German girls modelled their looks on her," to add in a note: "I owe this information to Hans Hesse of the University of Sussex. He suggested that the Inconnue became the erotic ideal of the period, as Bardot was for the 1950s. He thinks that German actresses like Elisabeth Bergner modeled themselves on her. She was finally displaced as a paradigm by Greta Garbo." (Alvarez, 156).

A German book "did more than anything else to spread the Inconnue's fame" (Phillips, 324): Reinhold Conrad Muschler's "sickly, though much translated best-seller" (Alvarez, 156) and tear jerker Die Unbekannte (1934, English translation 1935 as One Unknown). The short novella reads like a very long caption to the famous death mask, an over-sentimental attempt at explaining its mystery. Even Muschler's Inconnue herself repeats several times towards the end:"Es soll niemand wissen, wer ich bin" ("Nobody shall know who I am," 103, 118) – even if it is mainly to protect the Lord's repute. The story, which was also made into a film soon after its publication (1936, Frank Wisbar) was the Love Story of its day: on her way from Portuis to fabulous Paris, Madeleine Lavin, an innocent young enthusiastic poor provincial orphan of totally pure heart falls in love with Lord Thomas Vernon Bentick, a rich urbane and handsome British diplomat. They spend several romantic days together, most of them in Paris -- nobly resisting temptation -- until he has to leave for Egypt and his American fiancée and Madeleine goes straight into the Seine:"Ja Thom, ich bin's, ich komme. Ihr Antlitz lächelte verklärt, als man sie fand" (Yes Tom, it's me, I'm coming. Her face had a transfigured smile when she was found). Those last sentences give a good impression of the novella's predominating tone. But millions loved it and already the otherwise nauseated nameless reviewer from the Times Literary Supplement mentions a sale of over 100,000 copies for the first German edition. "This fact should cause the admiration and despair of the ever multiplying race of authors, for though they may envy, they can hardly hope to emulate its sincere, unaffected and quite nauseating sentimentality" (TLS 1935, 653).

D. Barton Johnson in an 1992 essay on "'L'Inconnue de la Seine' and Nabokov's Naiads" tells of how a German colleague of his "recall[ed] her tears on reading the work in the thirties" (231). Johnson believes that "Muschler's tale was almost certainly the immediate pretext for Nabokov's poem "L'Inconnue de la Seine," (232) written in June 1934 in Berlin, two month after Muschler's book was published. He sets out in his essay to show that "the figure of the drowned woman occurs throughout Nabokov's work. […] Beginning as the stock Russian folklore figure, the rusalka, the image evolves into l'inconnue with its admixture of Blok's neznakomka, and finally into Shakespeare's Ophelia. The introduction of these three images very approximately coincides with the three stages of Nabokov's creative life: the rusalka with the Russian period; the l'inconnue with the Continental stage; and Ophelia with the Anglo-American" (243). Walking the streets of Berlin, the narrator of a story from the same period ("Tiazhelyi dym," "Torpid Smoke," 1935) makes a more disparaging comment on seeing a picture framer's display, also there "the inevitable Inconnue de la Seine, so popular in the Reich, among numerous portraits of President Hindenburg…" (Johnson, 229). The Berliner Tageblatt of 4th November 1931 printed the story "L'Inconnue de la Seine" by Hertha Pauli, German writer and actress, sister of Nobel prize in physics winner Wolfgang Pauli (1945) and for many years the intimate friend of the Austro-Hungarian writer Ödön von Horváth.

Pauli and Horváth, had once planned to write a play together based on her story.

"Das Lächeln der Totenmaske hatte uns beide schon lange fasziniert. Aber zu dem gemeinsamen Stück war es nie gekommen, denn Ödöns "Unbekannte aus der Seine" besaß bald ein Eigenleben, wie alle seine Figuren, und ging ganz andere Wege" ("For a long time the death-mask's smile had fascinated both of us. But nothing ever came of the joint work, because Ödön's "Unknown of the Seine" soon gained a life of her own, like all his characters, and the play took a different path")

Hertha Pauli writes in her book of memories (Pauli, 60). The "Unbekannte" in Horváth's play of 1933 is a kind of seductress, one of the mysterious and soft kind, some critics read her in the tradition of such elemental female water spirits like Undine, the Lorelei, the sirens (Balme, 167). In the play the Unknown seems to appear from nowhere, a strange and unusual woman of "an impulsive spontaneity and quirkish teasing humour" (Balme, 168) like the elemental spirits of the fairy tales, an outsider in the world of Albert, former officer in a shipping agency, who embezzled money and, having used it all, is now planning with two others to rob a sum of 3000 from the shop of a clockmaker, unintentionally killing him but finding no money after all. The unknown woman time and again stresses that she herself has no money, placing her (except for Albert) even further outside society, which she will intentionally leave to drown herself when Albert dismisses their "relationship" as "ich hab halt einen Menschen gebraucht" ("I just needed someone for the moment," Horváth, 65) in front of his ex-girlfriend Irene, who still loves him and whom he will marry after all in the end. The Unknown's imagination is closely connected to water; she tells Albert: "Ich würde dich in den Schlaf singen, aber das Fenster müßte offen sein und wenn du hinausschaust, müßtest du grüne Augen haben, so große grüne Augen wie ein Fisch – und Flossen müßtest du haben und stumm müßtest du sein" ("I would sing you to sleep, but the window should be open and when you look out you should have green eyes, big green eyes like a fish – and you should have fins and you should be mute," 59). At the end of the play Albert and Irene, now married and with a son, see the death-mask of the unknown woman in the shop window of a bookshop and buy it for their bedroom.

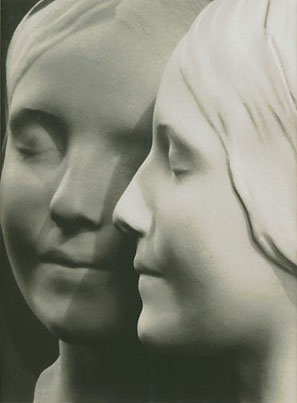

A fine collaboration between two people – the novelist Louis Aragon and the photographer Man Ray – occurred when at the beginning of the 1960s Aragon started the project of editing both his and Elsa Triolet's work in a joint edition titled Œuvres romanesques croisées. In the course of that project he asked Man Ray if he could contribute photographs for his 1944 novel Aurélien, and the result was eight photographs for the first and seven pictures for the second volume: they impressed Aragon so much that he commented:

"Mais le roman c'est Man Ray qui l'a écrit, jouant en noir et blanc du masque de l'Inconnue de la Seine" ("But in truth it is Man Ray who wrote the novel, playing in black and white with the mask of the Inconnue de la Seine," Pinet, 185).

Aurélien was the fourth novel in a cycle called Le monde réel. In contrast to the other volumes it mainly concentrated on two people: Aurélien Leurtillois, an idle 30-year-old Parisian – owner of the Inconnue mask – who after having served as officer in Wold War I is at a loss what to do with his life in the post-war years; and Bérénice Morel, the wife of a pharmacist from the provinces, the Inconnue of the novel. Although Aurélien doesn't make the connection between Bérénice and the death mask immediately, it is, nevertheless, at the very moment she closes her eyes that he recognizes his love for her.

"Alors, se penchant sur elle, il la vit pour la première fois. Il regnait sur son visage une sourire de sommeil, vague, iréel, suivant une image intérieure" ("Bending forward he saw her for the first time. There was a dreamlike smile on her face, vague, unreal, following an interior image," 89).

Later he also senses a similarity when looking at the mask and his reaction parallels the one just described. "Comme s'il le voyait pour la première fois. Pour la toute première fois" ("As if he saw it for the first time. For the very first time," 138). When finally in Aurélien's apartment Bérénice and the mask "meet", the text itself steps back for a moment, comes to a halt for a whole chapter, to contemplate "le goût de l'absolu" (the desire for the absolute).

"Qui a le goût de l'absolu renonce par là même à tout bonheur. Quel bonheur résistais à ce vertige, à cette exigence toujours renouvelée? Cette machine critique des sentiments, cette vis a tergo du doute, attaque tout ce qui rend l'existence tolérable, tout ce qui fait le climat du cœur" ("The one having the desire for the absolute from the start renounces any kind of happiness. What kind of happiness could resist this vertigo, this ever-restoring demand? The critical machinery of the sentiments, this malicious power of doubt, attacks all that makes existence tolerable, that makes the heart a happy one," 221-222).

The chapter's refrain reads "Bérénice avait le goût de l'absolu." The mask she holds breaks when Aurélien takes her in his arms, she will give him a new one, a mask of her own face, "Bérénice aux yeux fermés" ("Bérénice with closed eyes," 286) later, but, nevertheless, the two of them somehow don't manage to come together. Waiting wears Aurélien down and the night Bérénice flees to him, having left her husband, he is with another woman. His attempts to win her back are in vain; she will eventually return to her husband and he does what he never wanted to do, take on a job in the factory of his brother-in-law. Aragon added an epilogue set 20 years later during the Second World War. German troops are advancing. Aurélien feels that he could love Bérénice again and still does so, other than Bérénice. During a nightly trip she is killed by a bullet. In death she wears the Inconnue's smile.

In the end, the "real" Inconnue is genuinely unknown, and it is also unknown if the story of her mask is true or invented. "It is also possible that it never happened at all" Alvarez says (157) and tells the story of a researcher who followed the Inconnue's "trail to the German source of the plaster casts. At the factory he met the Inconnue herself, alive and well and living in Hamburg, the daughter of the now prosperous manufacturer of her image."

But this is just one version of the story, an attempt at demystification. On a idiosyncratic web site called The Framer's Collection, the Inconnue is identified as a music-hall artist of Hungarian descent called Ewa Lázló, murdered by one Louis Argon; a picture of her is here. And another commentator, René Vautrain, quotes someone who is quite sure he can prove the Inconnue is in fact a Russian from Saint Petersburg called Valérie (550). In her essay on the Inconnue, published in the catalogue of an exhibition of "last portraits" in the Museé d'Orsay in Paris in the spring of 2002 (Le Dernier Portrait) – also showing the Inconnue mask – Hélène Pinet recounts Jean Ducourneau's visit to the Parisian mouleur (maker of plaster casts) who had a shop in the rue Racine with many copies of the mask, the shop Rilke had allegedly passed by so often. A descendant of the mouleur told him that her father had always told her that the mask had been taken from a very beautiful model at the studio and that it was technically impossible to have taken a mask from such a cadaver (Pinet, 189).

Works cited

Alvarez, Al. The Savage God. A Study of Suicide. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1971.

Anonymous, "Review of Muschler's One Unknown," Times Literary Supplement 17 October 1935 (No. 1759), p. 653.

Aragon, Louis. Aurélien. Paris: Gallimard, 1947.

Benkard, Ernst. Das Ewige Antlitz. Eine Sammlung von Totenmasken. Mit einem Geleitwort von Georg Kolbe. Berlin: Frankfurter Verlags-Anstalt, 1926.

Blanchot, Maurice. Une voix venue d'ailleurs. Paris: Gallimard, 2002.

Boddaert, Francois. Petites Portes d'éternité. La mort, la gloire et les littérateurs. Paris: Hatier, 1993.

Friedell, Egon. Das letzte Gesicht. Zürich: Orell Füssli Verlag, 1929.

Goll, Claire, "Die Unbekannte aus der Seine," in: Zirkus des Lebens. Erzählungen. Berlin: edition der 2, 1976.

Horváth, Ödön von. Eine Unbekannte aus der Seine und andere Stücke. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 2001.

Johnson, D. Barton. "L'Inconnue de la Seine and Nabokov's Naiades," Comparative Literature, 44, 3 (Summer 1992), pp. 225-248.

Le Gallienne, Richard. The Worshipper of the Image, 1900.

Muschler, Reinhold Conrad. Die Unbekannte. Novelle. Bertelsmann Lesering, 1958.

Nin, Anais. "Houseboat," in: Under a Glass Bell and Other Stories. Athens: Ohio UP, 1995, pp. 32-44.

Pauli, Hertha. Der Riß der Zeit geht durch mein Herz. Ein Erlebnisbuch. Wien: Zsolnay, 1970.

Phillips, David. "In Search of an Unknown Woman: L'Inconnue de la Seine." Neophilologus 1982, July 66 (3), pp. 321-327.

Pinet, Hélène. "L'eau, la femme, la mort. Le mythe de L'Inconnue de la Seine," in: Le Dernier Portrait. Exposition présentée au musée d'Orsay du 5 mars au 26 mai 2002, pp. 175-190.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge. Frankfurt a.M.: Insel Verlag, 1982.

————. The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, transl. By M. D. Herter Norton. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992.

Schwartz, Vanessa R. Spectacular realities. Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris. Berkley: U of California P, 1999.

Sitwell, Sacheverell. "L'Inconnue de la Seine", Lilliput: the Pocket Magazine for Everyone 16(4), 1945, pp. 315-317.

Supervielle, Jules. "L'Inconnue de la Seine", in: L'Enfant de la Haute Mer. Paris: Gallimard, 1975.

Vautrain, René. "L'Inconnue de la Seine." L'intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, 195, June 1967, pp. 548-550.

The Recognitions || J R || Carpenter's Gothic || A Frolic of his Own || Agapē Agape