|

The Recognitions, Then and Now

|

||

|

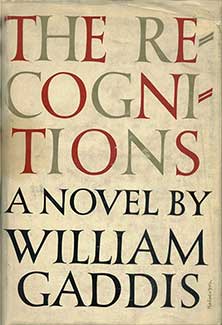

It’s an odd title, isn’t it—The Recognitions. In English we use the singular “recognition” often enough, but the plural form is rare, especially with that definite article in front of it. It sounds unidiomatic, like a literal translation of a foreign title (which it is). That’s the first potentially off-putting thing that a customer looking over the new releases in a bookstore 50 years ago would have noticed, and perhaps the only thing that was needed to cause the customer to pass over it and keep looking. For while some people are attracted by the rare and unusual, most people aren’t. But had a curious customer paused long enough to examine this new novel with the odd title, several other obstacles to buying it would have begun to appear, beginning with the cover. Unlike the majority of novels at that time, there was no pictorial representation of the novel’s setting, or of its principal character, or of a significant scene. Instead, just big block letters, alternating between red and gold against a plain white background, broken into correct but misleading syllables that made the odd title look even odder: THE RE- The lower half—A NOVEL BY WILLIAM GADDIS—would have meant nothing to the average reader. Gaddis had published only one brief essay before that, along with an excerpt from The Recognitions in an obscure literary magazine, so the name would not have provided any incentive to buy it. If, still undeterred, the customer would have picked the book up to examine it further, the next thing that would have struck her or him was the weight: 2 pounds, 7 ounces. 956 pages, the length of three or four standard novels. Again, some of us are instinctively attracted to thick, long books, but others are reluctant to make the large investment of time they require. So by this point, the huge novel with the weird title by an unknown writer would have scared off most customers. But for those still looking, further obstacles presented themselves. Flipping the book over, they would have seen a single blurb, by a Stuart Gilbert. The name would have been recognized by Joyce fans, for Gilbert wrote the first substantial book on Ulysses back in 1930, which had been reprinted in the early ’50s, but the average customer wouldn’t have known who he was. Gilbert evokes Eliot’s Waste Land and Joyce’s Ulysses, again catnip to us literary types but for the average customer a warning signal that this book would be difficult. And as one of our leading contemporary novelists assures us, people don’t like difficulty. But say a few customers in 1955 were among those freaks who regard difficulty as an invigorating challenge—as in a “difficult” golf course—rather than as an ordeal; those hardy few might have continued by looking at the front flap to learn more about the book. The first thing they would have noticed there was the price: Seven dollars and fifty cents! Nowadays that sounds ridiculously low, but in 1955 most new novels were priced at $2.50 to $3.00; so in today’s terms, $7.50 would be like paying $40 for a new book, an outrageous sum. Once they got over that shock, they would have found a fairly good description of the book, but on the back flap, there was no customary photograph of the author, a custom Gaddis metafictionally mocks on page 936 of the novel itself: “For some crotchety reason, there was no picture of the author looking pensive sucking a pipe, sans gêne with a cigarette, sang-froid with no necktie, plastered across the back.” By this point, for all the reasons I’ve given, nine out of ten customers would have put the book down. For those of us who regard The Recognitions as a masterpiece, it’s always been hard to imagine why the book was ignored when it first came out, but we have to remember that it entered the world, not as an obvious masterpiece, but simply as a new product fighting for the customer’s attention in the marketplace. Whether by accident or design, the book placed a number of obstacles between itself and book customers during those first crucial minutes when they browse the table full of new releases. And if that one out of ten who was still interested persisted with his or her investigation, what would they have encountered upon opening the book? Well, the first thing they would have seen is the book’s motto. In Latin. By someone named Irenaeus. Not a strong selling point, unless you’re a big fan of early church fathers. Next thing is an epigraph. In German. At least this one is by Goethe, a name most people would recognize. Now, if they made it over all those obstacles and actually read the first paragraph of the novel, they would have been rewarded with an elegant, sardonic paragraph that sends up a flare announcing that this is indeed no average novel. The better- read may even have noticed the paragraph ends with a subtle allusion to a line from one of Robert Browning’s poems, an indication of Gaddis’s allusive manner. But if instead they had flipped the book open and read a paragraph at random, they may have been confronted with something like this:

OK, put the book down. I don’t think Uncle Dwayne would want this for a birthday present. Now: there may have been some who remained undeterred by all these obstacles and even liked what they saw in Gaddis’s novel, but were reluctant to shell out the enormous sum of $7.50 until they learned what the critics thought of it. Surely, the respected members of the press would tell them whether this book was worth their time and money. The novel received 55 reviews over the next few months, and 2 or 3 of them were actually fairly positive. The reviewer for the Amarillo News liked it, and so did the guy for Library Journal. (That was Herbert Cahoon, for many years the bibliographer for the James Joyce Quarterly, and thus used to that kind of writing.) The rest damned and blasted the book, working it over with one of the worst critical muggings in literary history. For the sordid details, read Jack Green’s Fire the Bastards! But it’s too easy to blame those bastards . . . I’m sorry, those reviewers for scuttling The Recognitions in 1955. They were typical members of a dominant literary community that was hostile to innovative fiction in general. Jack Kerouac couldn’t find a publisher for his first, more experimental version of On the Road, and had to write a more commercial one to get it published. (The magnificent original version, entitled Visions of Cody, wouldn’t be published until 1972, three years after his death.) Vladimir Nabokov had to publish Lolita in Paris at first; no American publisher would touch it; same with William Burroughs, whose Naked Lunch was published in France in 1959 but not in America until 1962. Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer had likewise been published in France back in 1934, but banned in America until 1961; same with Lawrence Durrell’s decadent first novel, The Black Book, published in Paris in 1938 but not available here until 1960. And of course D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was written even earlier but was not allowed into America until 1959. Felipe Alfau wrote a brilliant novel entitled Chromos in 1948 but couldn’t find a publisher for it at the time, and had to wait more than forty years to see it in print. And who knows how many other amazing novels from the 1950s never even saw the light of day because of the provincial, conservative nature of American publishing at the time. To be sure, there were a few American publishers—like Grove Press and New Directions—that were bringing out unconventional works, but for the most part, such fiction was unwelcome. Innovative authors writing in foreign languages fared even worse; American publishers simply assumed its readers were not yet ready for their daring works, and so Americans were kept in the dark about a number of fascinating authors. Jean Genet, for example, published all of his transgressive novels in France in the late ’40s and early ’50s, but it wasn’t until the ’60s before they’d be translated into English. The great German writer Arno Schmidt began writing his experimental novels during the late ’40s, but none of them would appear in English until the late ’70s. Stanislaw Witkiewicz’s 1930 novel Insatiability—sort of Poland’s answer to Ulysses—likewise didn’t arrive here until the 1970s. Consequently, there was almost no context, and no perceived market, for such a novel as The Recognitions in the sheltered literary world of the Eisenhower ’50s. In fact, in light of all this, it’s something of a miracle that The Recognitions was published at all. The novel is laced with obscene language, which was still rare at that time in fiction, and is fiercely blasphemous. The character Anselm ridicules Christianity mercilessly throughout the novel, and Gaddis himself has lots of fun with Catholic stigmatics and other religious nuts. Reverend Gwyon spends most of his time exposing Christianity as a counterfeit of earlier religions. And there’s that scene toward the end when the phony novelist Ludy has an attack of the runs and afterwards wipes himself with pages from a nearby book—the most prominent book you’d expect to find in a monastery. The novel also has a number of homosexual characters and transvestites; not only is their presence unusual for a 1950s novel, but they’re actually treated fairly nicely, which was almost unheard of back then: the unspoken rule was that any homosexual characters had to come to a bad end, but Gaddis has a few of them getting married and heading off to Europe for a honeymoon at the end. A number of characters use drugs, which was still fairly rare in “respectable” novels back then. And finally, the novel is incredibly frank in its treatment of sexuality; not only is there rampant promiscuity, but there are scenes featuring masturbation and even bestiality. (Who could ever forget the moment when the servant girl Janet is caught in the act with a bull?) So it’s not surprising that the reviewers were shocked by Gaddis’s novel and felt compelled to denounce it. They were presumably unfamiliar with novels of the sort I mentioned earlier—those by Genet, Durrell, Schmidt—which were already treating these topics with the same bravado, and so Gaddis’s novel must have seemed like a weird aberration, and not anything you’d recommend to the average reader. But how about the academic community, those who in the ’50s were teaching and studying Joyce’s Ulysses, Faulkner’s more experimental works, Céline’s novels—why didn’t they pounce on The Recognitions and praise it? You would think those who liked intellectually challenging writers like Joyce and Eliot—not to mention older writers like Melville, Sterne, Rabelais—would have championed the work. But unfortunately, academics in the ’50s still had a wait-and-see attitude towards new fiction: a book had to pass “the test of time” before they risked writing about it. Even a book as stupendous as Ulysses inspired very little academic criticism at first; it was published in 1922 but it would be thirty years before the Joyce industry got into gear; same with Faulkner, Eliot. Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano remained under the radar for decades. Samuel Beckett’s novels were neglected at first. And of course little or no contemporary fiction was studied in English classes in the ’50s. It wasn’t until the 1960s that some academics felt it was OK to write about recent novels, and it was J. D. Salinger, of all people, who made that possible: academic books began appearing within a few years of the publication of his books, which was unheard-of until then. But even so, writing about current fiction was considered a kind of slumming, a little vacation until you returned to the real stuff. In this regard, as in so many other ways, The Recognitions was simply ahead of his time, andwould pretty much be ignored by the academic community for the next few decades. And finally, we have to remember that the ’50s were . . . well, the ’50s. It was a very conservative era—it’s a cliché but true—and the last thing anyone wanted then was a blasphemous, foul-mouthed, erudite, multilingual, liberal, thousand-page novel denouncing the American way of life as hypocritical and phony. In later years, Gaddis himself admitted that it was naïve of him to think that his novel would be welcomed with open arms and that he would be thanked by a grateful but chastised public for showing them the error of their ways. It was the wrong time for his brand of social criticism and black humor, his kind of high-wire literary showmanship. Cracks were beginning to appear in the façade of the Eisenhower ’50s, and innovation could be seen in some of the other arts: it was an exciting time for painting and sculpture, jazz was getting more abstract and experimental, rock music exploded onto the scene, and the Beats yanked poetry out of the academy and took it to the streets. But most novels still resembled their Victorian predecessors in form, and it wouldn’t be until the ’60s that some readers began to realize fiction could be as innovative as other art forms. Had The Recognitions been published in 1965 instead of 1955, things may have been different. It might have won the same acclaim that greeted Pynchon’s V., Heller’s Catch-22, Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoos Nest, and other unconventional novels of the ’60s. Who knows? The Recognitions was ahead of its time, and the literary establishment back then crushed Gaddis in much the same way that the church on the last page of the novel crushes the true artist Stanley; but as Gaddis predicted in the last line, his work would survive. And as all of us gathered here today will demonstrate, “it is still spoken of, when it is noted, with highregard.” |

|||

index || site map || site

search || Gaddis news

The Recognitions || J R || Carpenter's Gothic || A Frolic of his Own || Agapē Agape |

|||